Social and Cultural Institutions

Work, Labor and Pushcarts (1880-1938)

...when we came in ‘58 it was a bad time. Not much work. We went to the office to get a job, they wouldn’t hire because they told us they were laying off their girls.

…I was amazed with the place, it was beautiful. That was the first thing I fell in love with. That shop. So beautiful. I said, can I walk around and look. He said sure. As I was walking around there was an artificial fireplace...that fireplace reminded me of the one I had in Italy because we had no fireplace, nothing here. It was a very cold house. And I started to cry.

This man came across and said, I guess, “What’s the matter” in English. Then the guy that took us there, he came and said to the guy in English that we had just come from Italy and that we were looking for a job. That was the owner, Mr. D., he said “Where are you from?” in Italian. I told him and he said, “You’re my neighbor, in Italy. I come from Italy.” I didn’t know he was the owner.

He said, “Would you like to work here?” I said, “This is beautiful. It reminds me of Italy.” He said, “Why are you crying?” I said, “The fireplace reminded me of the one I used to have in Italy, but mine was real.” He said, “Would you like to work here?” I said, “I’d love to but they wouldn’t give me a job.”

He said, “Come in Monday morning and you start working.” And that’s how I got the job.

Loreta Caputo, February 23, 1979

Three Generations of Italians

Rhode Island, prior to becoming the inciting location of the American Industrial Revolution, was based in a maritime trade economy. Much of this was upon the Trans Atlantic Slave trade up to its abolition.1 At the turn of the 19th century, Samuel Slater introduced water run cotton mills to America (1793) and brought industrialism to America. These new machineries raised the industrialist to prominent means of garnering wealth.2

The 19th Century was marked by the development of factories in Providence. Over the century factories developed alongside the Moshassuck in Providence, and changed the origin of work itself. Jobs developed requesting cheap and long, arduous labor, preying on impoverished immigrants.3 This is where 19.9% of Italian American laborers in Rhode Island cited as their workplace in 1915.4 Italian immigrants entered the workplace with temporary intentions. As many as 5,000 men per year would return to Italy during 1914-1919.5 Money and employment were the primary focuses as they left an Italy adored, but financially unstable. America could provide the work they needed.

Although most Italian immigrants had come from rural farming areas, few continued in that trade. Attaining land was a difficult and expensive process at this point of Federal Hill’s development. Industrial labor appealed to them for its security and availability in opposition to scarce factory existence in Italy.6 Where both women and children had worked in Italy with men on farms, women working outside of their homes threatened the patriarchal system of Italian lifestyles. The work was done out of necessity, as there was no family wage adequate to provide for an entire family if they were not working. Children too were subject to becoming wage earners, although could not be reliable due to assimilation, truancy laws and the formats of labor presented to them.7

Storefronts and Pushcarts

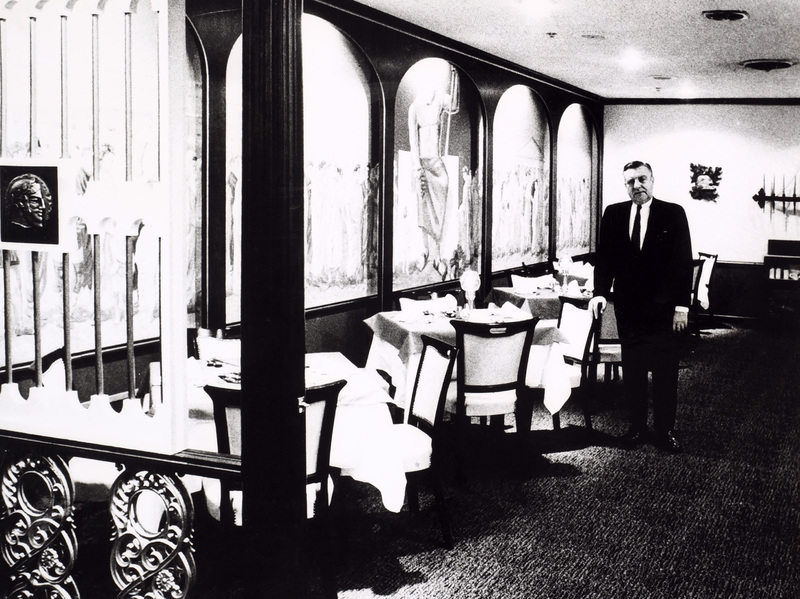

Some found a pursuit towards the middle class early on, joining the bourgeoisie in varying ranks. Some ran restaurants, cornerstores and barbershops, or became tailors, funeral operators, or other services for the community. Italian-run business on the Hill incentivized community support for survival of Italian identity in America. Certain terms of loyalty to ones neighbors in Italy or Italian products at all arose and were attained by the shopekeepers to keep business away from the rising chain department stores.8

By having Italians in the operating hierarchies of labor, some suggestions of stability were formed as alliances. Still, Italian bourgeoisie were minimal in numbers on Federal Hill, and Italians were underrepresented across professional office.9 At first, having ethnically Italian stores on Federal Hill was the only way of retrieving Italian goods. Displayed through the reaction of the Macaroni Riots, these establishments often only served the middle-class. A growing Italian-American bourgeoisie could not function with nor uplift working class counterparts, but kept Italianness alive.10

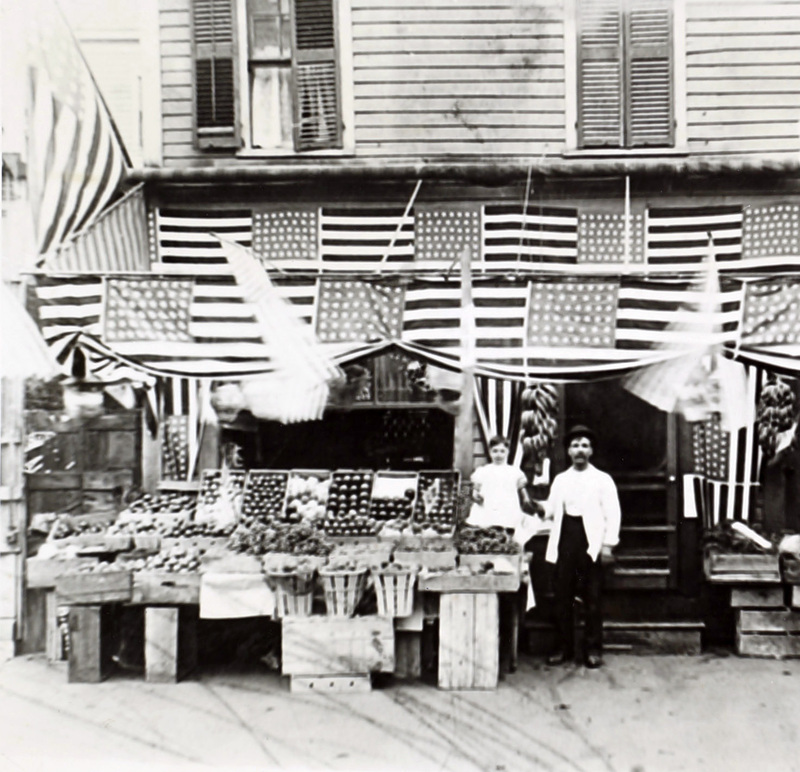

Those who did keep to agricultural production found themselves selling their goods and wares in pushcarts - movable stands in which an informal transaction of their wares was directly made. Most pushcarts set up in the heart of Federal Hill, along Balbo (DePasquale) Avenue and Spruce Street, where restaurants and the public could purchase fresh fruits, vegetables and other products.11

...you would go there and there would be pushcarts on both sides of the street with big, big covers in case it rained, They would sell any kind of fruit and vegetable you can name, and reasonable. And you go there on a Saturday night, you get bargains galore...I remember the Holy Ghost would have three or four [festivals] every summer, you know...on Knight St. right near Holy Ghost they would have a band concert there and they would have pushcarts. They were selling all kinds of exotic nuts and fruits…

I'd say on a Friday night and Saturday, you couldn't move on Federal Hill. There’s so many people that would go shopping. Business was soaring. Everybody was doing business. Pushcarts on Balbo Ave. which is DePasquale Ave. now...they would be loaded with push carts and every store on both sides of Atwells Ave. down to the Holy Ghost Church were humming.

Joseph Apicerno, June 28, 1978

Federal Hill Project

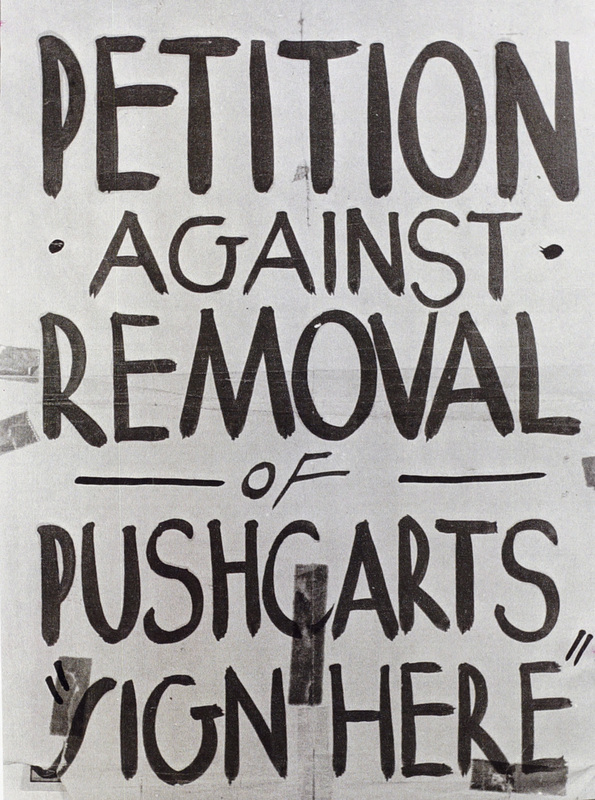

From 1935-1942 a ban on pushcarts was promoted by the ward’s Alderman, Thomas S. Luongo. He, with permission from Providence Mayor James E. Dunne, removed pushcart vendors from the Balbo Avenue area with police enforcement. The neighborhood came together to protest, hanging petitions and holding rallies in order to retract the legislation.12

They succeeded, and Balbo Avenue was later redeveloped. However, due to age and struggle in the vastly changing markup of Federal Hill, the pushcart vendors would mostly fade away following the seven year fight.13 For the period of their existence however, these vendors served as a foundation of physically communicative life of Federal Hill residents and bridged the gap between life in Italy and the new sorts of labor and living seen in the United States.

Religion and Federal Hill

The Catholic churches of Providence, prior to Italian immigration, were also fronted by ethnic identity. Rhode Island, had a Protestant population who had reservations and active violences against Catholicism.14 Due to Irish immigration in the 19th century, churches in the Federal Hill neighborhood such as St. Mary's (1853, 1901) and St. John's (1871) were developed to serve the Irish Catholic population.15 In 1889, the Church of the Holy Ghost was established by the Providence Bishop Harkins to satisfy the newly Italian Catholic neighborhood. Construction was completed by 1901 at the corner of Knight and Atwells Avenues.16

The early years of the Holy Ghost faced several conflicts between the parishioners and its clergy. Established under a newer and northern Italian sect of Catholicism (the Scalabrini Brothers), the church provided too many discrepancies for its larger parishioner base of southern Italians. Unfamiliar with the practice of offerings made in the west to fund religious institutions and dissatisfied with restrictions made on informalized feast and Saint days, the community accused Reverend Belliotti of corruption and petitioned for his replacement in 1906. The church refused.17 Two more Reverends would be argued to be pushed out over the next twenty years until a suitable Scalbrini was found; Friar Flaminio Parenti. During the transgressions of mistrust, a second parish was formed on the Hill, Our Lady of Mount Carmel in 1924.18 Tensions mostly died down as the divisions of Italian ethnicity and experience weakened through the homogenization of Italian American culture.

The church became a pillar of the community, and paralleled the efforts of other social institutions by providing community space, activities, and religious services.19 The Holy Ghost eventually assumed organization of feast days in relation to particular Saints and Italian icons. The entire neighborhood would partake and celebrate with their Italian identity across the avenue, stemming from the Church’s steps. For every Columbus Day (the largest celebration)20 there were several other specific feasts and parades through the year. Each village in Italy had different associations but would celebrate with their past and new neighbors. Weddings and sacrament days were also massive processions that filled the streets of Federal Hill with the Italian community.

…of course you didn’t eat before receiving communion. Between that and nerves, after that, about a week or two after we made the first communion, we always had a procession and it would go on for a couple of hours. It would go to the length of Knight Street and it would take in all the side streets like Glesser Street, Tell, Ring, Grove – we took in all those side streets – right down to Ridge Street, and the people would be out either on the windows or on the sidewalks – they would be lined up just like they would be downtown for the Columbus parade…

The women would bring out all their beautiful spreads some of them had even big tablecloths, nice tablecloths and they would hang these from the windows, and this was the most beautiful sight to see these spreads or these tablecloths hang from these windows to show honor to the Blessed Virgin when she was coming by. The men would carry her on a stand and children would be lined among the sidewalk…they always had baskets of flowers and they would toss these flowers and the petals of the flowers. They would toss them out on the street as the procession was going by.

People used to make the sign of the cross. They didn’t make just a little cross with their fingers and kind of hide that they were Catholics or hide the fact that they were making the sign of the cross. They actually made the sign of the cross - the complete sign from the forehead to their chest, to the left side and the right side.

Cammille M. Prattico Charette, June 21, 1978

Federal Hill Project

Catholic “lay societies” also functioned as social involvement of the parish and its community formed through Catholicism. Many more women took place in these societies due to the patriarchal nature of mutual aid groups and fraternal orders. The merging of oneself as a religious self in a community fostered ties of commitment not only to the church but the persons of it. This praised the idea of bringing the moral values of the church into the life of the immigrant.21 Bonding over issues of the role of the family, labor, and more created an shared Italian identity that privileged this through piety.

Ethnic Identity and Politics

Many times [Italians are] described as a people who resign themselves to their fate. No it’s not that. It’s total indifference. For example, they won’t get excited about politics. They won’t get excited about politics because politics means nothing. Politicians are very unpopular in Italy. I dare say they are getting more and more unpopular in every part of the world. So they’re not resigning themselves to their fate or fatalistic.

They are merely demonstrating their indifference to the life all around them. There’s so much individuality ...The Italians I would say, especially in southern Italy are a total undisciplined people. They feel they don’t need politics, or any kind of discipline. They have this discipline.

...the American navy gave them the impression that all Americans live in this rich atmosphere. It was strictly a Hollywood production. But the Italians, not knowing that this was just a make-believe thing, they would never suspect that they were being cheated of reality. So they actually learned the truth mainly from hearing and finding out through the T.V.

They didn’t expect to see poverty. They expected to see all the streets paved with gold

Joseph Marciano, June 29, 1978

Federal Hill Project

The political world most Italian migrants left was divided. At the beginning of Italian migration to the west, Italy had only been 20 years united, and southern Italy unrepresented by its northern-enforced unification. Leaving was made for reasons of stability and necessity.

By the time the Italians arrived to Federal Hill, a practice of vote buying had already originated. The Republican party had a firm grip on Rhode Island for several decades due to the conditions of the population and intentional protection of Anglo interests.22 The newfounded constitution and failures of the Dorr Rebellion23 still left all immigrants with little voting power, because it still organized around the ownership of property and worked in tandem to limit voting eligibility of all non-essential and non-American peoples. Most of this was directed upon limiting eligibility by property ownership and time spent in America.24

These laws were also intentionally set to barr immigrants from seizing control of public office. Initially the parties both would not cater to immigrants, as second class citizens would not be of use to them in their small numbers. Upon the rise of immigrant populations such as the Italians, whom in 1930 would makeup 18% of the Rhode Island population, political parties changed their tactics to promote and reach out to these populations.25

Early Italian American voting trends leaned Republican, and attendance remained weak. Some of this is in obvious consideration to the legal precedents, and other pieces attuned to a need to redefine one’s own ethnic ties.26 The conflicts of World War II and Mussolini’s wars abroad complicated Italian American identity. Many recent immigrants sent their rings, watches, and money to the war efforts and condemned America for their entering on the allies.27 Others, upon seeing the actions of the fascists, fleeing them, or hearing news of the atrocities of Mussolini’s ties with Hitler, resonated antifascist disgust with their homeland. The complications continued in their new home, with the American identities they had dreamed of rarely presented as options.

More often than voting, Italian Americans organized outside of electoral politics around specific issues - the Macaroni Riots, actions against the church, pushcart protests, et cetera - that affected Italians and their neighborhoods. A more broad unification was made by nationwide reactions to the 1927 executions of Sacco and Vanzetti. In Providence’s case, this resulted in the seeing of an apparition of the Virgin Mary on Federal Hill and questioning the validity of the state’s case as it stood against God.28

Providence Republicans began to reach out to and appoint candidates to their ranks. This was useful to maintaining control and ensuring the rising population’s votes. Certain members of the community became spokespersons for these politics, and worked with the party to ensure votes come September. The church and newspapers too chose candidates they wanted to support and pushed voters towards them.29 Democrats began to do the same, finding Italians to recruit and use to win the votes of the neighborhood.

1 For more information, please refer to: Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark work: the business of slavery in Rhode Island, New York: New York University Press, 2016; Charles Rappleye, Sons of Providence: the Brown Brothers, the slave trade and the American Revolution, New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006; Craig Steven Wilder, Ebony and ivy: Race, slavery, and the troubled history of America’s universities, New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2013; Neocolonial Providence: Nonprofits, Brown, and the Company Town, Providence: Storm the Tower, 2014.

2 George S. White, Memoir of Samuel Slater, the father of American manufacturers; connected with a history of the rise and progress of the cotton manufacture in England and America, New York: A.M. Kelley, 1967.

3 Luconi, Stefano. The Italian-American Vote in Providence Rhode Island, 1916-1948. New Jersey: Farleigh Dickinson University Press and Rosemont Publishing & Printing Corp (Associated University Presses), 2004, pp. 24-25.

4 Ibid pp. 26.

5 Ibid pp. 22.

6 Ibid pp. 24-30.

7 Smith, Judith E. Family Connections: A History of Italian and Jewish Immigrant Lives in Providence, Rhode Island 1900-1940. State University of New York Press, 1985, pp. 75-82.

8 Smith, Ibid; Luconi, Stefano. “Ethnic Shops versus Chain Stores: Retailing among Italian Americans in Providence in the Interwar Years.” Rhode Island History, vol. 63, no. 1, 2004, pp. 3-4.

9 Carroll, Leo E. “Irish and Italians in Providence, Rhode Island, 1880-1960.” Rhode Island History, vol. 28, no. 3, 1969, pp. 69-72.

10 Carroll, pp. 74; Luconi, “Ethnic Shops…” pp. 9-11. This section also addresses the exploitative and predatory actions taken by these businesses to support fascist developments in Italy. By securing fellow Italian wealth, businesses were able to place themselves as the mainstay of the community, rather than a piece of all parts. Later sections will address this.

11 Muratore, Joseph R. "The Pushcart Struggle 1930-1942: Board Bans All Pushcarts from Balbo Avenue by October 1, 1937 (Part VI)." The Echo [Providence] 06 Sep. 1979: pp. 20-21. Print.

12 Muratore, Joseph R. "Federal Hill Landmarks: The Pushcart Struggle 1930-1942 (Part IV)." The Echo [Providence] 23 Aug. 1979: pp. 44; "The Landmarks of Federal Hill: The Pushcart Struggle 1930-1942 (Part VII)." The Echo [Providence] 20 Sep. 1979: pp. 20-21; Ibid.

13 Muratore, Joseph R. "Federal Hill Landmarks: The Pushcart Struggle 1930-1942 (Conclusion)" The Echo [Providence] 04 Oct. 1979: pp. 20-22; Ibid.

14 Strene, Evelyn. Ballots and Bibles. Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church in Providence. Cornell University Press, 2004, pp. 218-235.

15 Wm. McKenzie Woodward and Edward F. Sanderson. Providence: A Citywide Survey of Historical Resources. Rhode Island Historical Preservation Commission, 1986, pp. 138, 155-156; A note from the author: St. John’s closed in 1991 and its Reverend and pastor merged with Our Lady of Mt. Carmel. The space St. John’s once occupied is now a small park. Our Lady of Mt. Carmel is also closed at the time of this writing (2018) and has been since 2015. (Neil Swidey, “A sad day in the history of St. John’s: Federal Hill church closes after 121 years.” Providence Journal, 1 Jul. 1991, pp. C-1; A. P., “Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Church on Federal Hill to close indefinitely,” RI Catholic, 5 Nov. 2015, Web.)

16 Woodward and Sanderson, pp. 138.

17 Francesconi, Mario. The Scalabrini Fathers of North America 1888-1895. New York: The Center for Migration Studies of New York, Inc, 1983: pp. 57-59; Strene,

18 Woodward and Sanderson, pp. 138.

19 Strene, pp. 120-131.

20 A note from the author: I highly recommend these two pieces to examine complicated Italian idolization of figures like Columbus and Mussolini at least at their origin: Avanti Popolo: Italian American Writers Sail Beyond Columbus, edited by Italian American Political Solidarity Club, San Francisco: Manic D Press, 2008; Vincent M. Lombardi. “The Response to Fascism.” The Italian American Working Class. Edited by Pane e Lavoro. The Multicultural History Society of Ontario, 1980.

21 Strene pp. 127-131, 148-152.

22 Strene, pp. 13-35; Luconi. Itaian American Vote... pp. 29-36.

23 A series of confrontations between a small group of secessionists and the state - for more information refer to: Gettleman, Marvin E. The Dorr Rebellion: A Study in American Radicalism 1833-1849. New York: Randomhouse, 1973; Chaput, Erik J. The People’s Martyr: Thomas Wilson Dorr and His 1842 Rhode Island Rebellion. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013.

24 Strene pp. 13-35; Luconi, Italian American Vote... pp. 31.

25 Strene pp. 7.

26 Strene pp. 48-55.

27 Strene pp. 146-147.

28 Strene, pp. 230-235; “Federal Hill in Uproar as ‘Angels, Saints’ Appear.” Providence Journal, 10 Aug. 1927, pp. 3; The executions of Sacco and Vanzetti to this day are theorized to have been based on condemnations of immigrants - Italians in this case - as well as political affiliation. This spread rage throughout communities of Italians nonetheless differentiating political status.

29 Strene; Luconi, Italian American Vote... pp. 37, 39-40, 45-49, 56. Both of these works examine this history much closer than I could give credit and time to. They are highly reccomended.