Renewal vs. Redevelopment

Urban Renewal

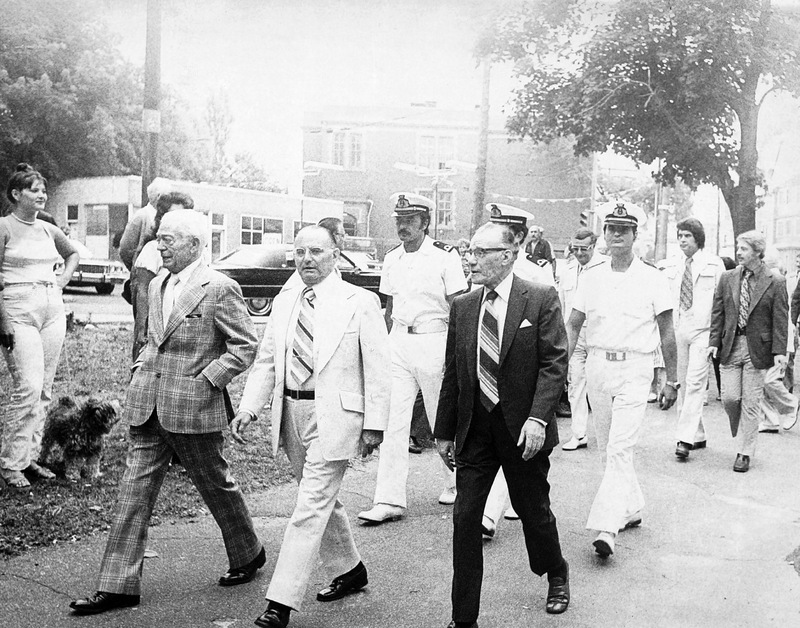

Antonio Pace, Cavaliere Joseph Muratore and Cavaliere Vincent Lentini, 1979

"Where it all began," 1979

The 1940s to the 1960s are a time of decline in Federal Hill. The area, consistently marked at the time by ignorance from government powers, was rife with crime, violence and architectural degradation of the area.

In many ways, the rise of blighted buildings characterized the end of industrial development. Factories closed, or burned down, or became minute in their production and available labor pursuits. Providence was overcast by East Side and College Hill developments. Federal Hill was left to only develop further as a slum. Tenements were left unattended by landlords, falling into disrepair. These buildings became rife with vermin, a rise of stray dogs, insects and rats plagued the neighborhood.

The Providence Redevelopment Agency took action under the clause of urban renewal, believing in the destruction of buildings and slum clearance. The development of Interstate 95 and revamping of the train lines entirely wiped out a growing Lebanese neighborhood off of Dean Street.1 Many of the most infested buildings remained, only closed off; untouched. Providence Redevelopment Agency and the City of Providence consistently were making promises they would not keep. When destruction of housing would occur, no plans were set to build anew, decreasing the available space to live in.2

Crime on the Hill was a worsening problem. Yes, the obvious account of crime in form of the Patriarca crime family, but also more general felonies and misdemeanors: vandalism, assault, burglary and car break-ins. Police presence was little to none, leaving no modes to address such community-based issues to the state for the peoples of Federal Hill.

The neighborhood’s supporters of previous years started declining during the depression. Italian businesses struggled to keep up with the changing world and accessibility of chain stores’ prices.3 These stores appeared to cater to the middle class, only one notion of many forgettings of the poor of the neighborhood, its immigrant history and its struggles to exist at all.

Lay societies and the church continued to play a role, but had little ability to take actions. The tensions of its beginning, set by ethnic differentiation within Italian identity had been assuaged to homogeneity.4 Mutual aid societies no longer had the affiliations and membership they once needed, nor served for certain properties of new immigrants, since immigration had slowed.5

Federal Hill House too suffered two significant changes - where its building burned down in the 70s and its attentions changed yet again - due to the small incoming migrants. Federal Hill House slightened its programs and physical presence on the Hill by the limited space available.6

Persons’ houses were being incentivized in bought by the Redevelopment Agency but no one saw the financial investments returned to them.

Federal Hill was left to powerlessness, and those who moved up the ranks of class began to leave the Hill for the suburbs - the exodus creating a vast de-collectivism of identity and presence. From 1950-1960 it’s estimated that eight thousand people would leave Federal Hill on notions of white flight.7 Poor Italian Americans could not invest in their community, and the businesses of those with money acted on the learned identity of the American Dream. It is also understandable that this made the neighborhood angry, and methods to lash out at the city officials developed to repair and redevelop their neighborhoods.

National Organization of Italian Americans

In 1969, Gino Maini, then director of Federal Hill House, hosted “gripe sessions” at the Holy Ghost. Maini’s intention was to have community discussions about the effects that urban renewal was having upon the neighborhood. Lacking organization, demands, courses of action, and becoming personal debates caused these to be ineffective ways to address the situations at hand.8

In 1972, after Maini left Federal Hill House, he reached out to the National Center for Urban Ethnic Affairs. Upon receiving funding, Maini formed the National Organization of Italian Americans. His plan was to use the funds from NCUEA to fund independent projects that would be able to address the concerns he saw and specify actions.9

At the end of 1972, the National Organization of Italian Americans sought to provide social services, promote economic development through job training and referral services, develop low and middle income housing, preserving Italian American heritage, and to communicate with other ethnic groups to combat discriminatory practices.10 These goals mostly acted as words until the hiring of Dave Beckwith in 1973 who modeled and organized more concentrated spaces under the National Organization’s received funds - the block clubs.

Organizing Block Clubs

In response to urban renewal, individuals were incapable to take direct action against the destruction and lack of consideration affecting Federal Hill. Beckwith’s knowledge he brought from his work with another Providence agency - People Acting through Community Effort - suggested the idea of banding specific sections of Federal Hill together.

A block club, or simply a community uniting of a specific street or area, helped specify the problems affecting smaller areas. Although the problems each Federal Hill block club faced were similar - absentee landlords, abandoned property, crime, and lack of or deteriorating public space, by separating these issues the particular components affecting each area could be addressed.11 The three earliest accomplishments of these actions set a standard for resolutions to come: New Homes for Federal Hill, New Bridgham School, and demolition of the Bradford Street bathhouse.

New Homes for Federal Hill was a plan by the National Organization of Italian Americans and block clubs to establish new property for family housing on the Hill and the destruction of the properties that the Providence Redevelopment Agency condemned but would not demolish.12 This left these buildings empty and as fire-hazards. In order to revitalize the neighborhood, adequate housing had to be made available. Organizing alongside the entire community, funding was secured from collective notions and governmental aid. The first home sold was in 1975 at a loss. The fight for gaining funding for future housing developments also came with terse relationships with the banks who were unwilling to back housing developments beyond single-family dwellings, and loan money the state had required not being given to the banks of the area, nor members of the neighborhoods.13

Federal Hill Parents for a New Bridgham addressed the issue of Bridgham Street School. The city of Providence had received a $7.5 million bond to renovate schools in the area. Bridgham Street School was deemed the last of three to gain aid by Mayor Doorley and a committee assigned.14 Upon learning this news, the Parent Teacher Associations alongside National Organization of Italian Americans leaders, put press and parental presence on City Hall, the committee and Doorley to address Bridgham Street first. Where Asa Messer Elementary School is today, the parents pressured both finding the space for Bridgham to exist on the plot of land, and securing contractors and architects to prove the validity of its space.15 Political action and pressure such as stating “Don’t play with our children’s future” forced the committee to oblige Federal Hill Parents for a New Bridgham’s requests. Ground was broken on June 19, 1974.16

The demolition of the Bradford Street bathhouse was organized by Bradford Area Neighbors - one of the smallest but most tight-knit block clubs. In Federal Hill’s past, before access to running water was a given within houses, the bathhouse had served the neighborhood not only as a resource but as a space of community interaction. In 1974 however, the bathhouse was only home to rats.17 This space was not only heightening the unsanitary status of Federal Hill, but also was at the opposing end of the neighborhood from Holy Ghost, and closest to where downtown Providence was trying to thrive. Pressures were put on and promises made by city officials, but it wasn’t until January 1975 when $34.8 thousand would be dedicated to the demolition.18

We used to have the old bathhouse there at one time where years ago people didn’t have showers or tubs and you were able to go there and take a bath. But then I would say within the last fifteen or twenty years they stopped using it. It was just sitting there doing nothing. I myself would have liked to have seen it restored as a building so that senior citizens or almost anyone could go sit there and play cards, draw, or whatever. But the neighbors around that area wanted it torn down because it was being vandalized so they decided that they would like it completely torn and the results is Garibaldi Park…

...there used to be an older field there I remember with a little bit of a pool there. When I was a child I remember wading there and they used to call it Garibaldi Park then. But now, it’s a new Garibaldi Park. We have the grass, the benches.

Eleanor Dyer, June 28, 1979

Federal Hill Project

In March, Mayor Cianci was brought to the demolition site, thinking he was only making a public appearance, but Bradford Area Neighbors implicated his promise to replace the site with a park and Cianci was forced to comply. The park would finish completion in May 1975 and be formally named Garibaldi Park after the Italian general.19

Some other smaller action include the block clubs uniting against the proposed closure of fire stations in the Federal Hill area by Doorley to save money. When 800 people came to state their disapproval, the city had to rescind its notion.20 Ring Street Block club secured a renovation of a public park and lot cleanups by putting out personalized surveys which the city was not doing to gain public input.21 Ridge Street forced promises that the development of Route 6 would not cause serious property damages to the houses who lined the side adjacent. A protective barrier was built where the state was first going to do nothing.22

Block clubs filled potholes, had street signs put in by the Department of Transportation, forced public protections and service, and coerced public officials to recognize their neighborhoods. Problems started to arise in certain actions and organizations - particularly among the merger of Federal Hill organizations to Center for Ethnic Neighborhood Organization

Redevelopment was composed of actions taken by the people of Federal Hill for their decided shared-needs.

1 Lynch, Robert P., et al. Federal Hill Case Study The Story of How People Saved Their Neighborhood. New England Neighborhood Revitalization Center, 1978, pp. 3.3-3.4, 8.2-8.3; United States. Federal Highway Administration Rhode Island Department of Transportation. Draft environmental impact statement : Route 6, Killingly, CT. to Johnston, R.I. 1985. Print.

2 Ibid, pp. 8.4-8.9; Wood, Charles R. Community renewal program. Providence: Blair Associates, 1964.

3 Luconi, Stefano. “Ethnic Shops versus Chain Stores: Retailing among Italian Americans in Providence in the Interwar Years.” Rhode Island History, vol. 62, no. 1, 2004, pp. 3-15.

4 Lynch pp. 11.1.

5 William J. Jennings Jr. and Patrick T. Conley. Aboard the Fabre Line to Providence: Immigration to Rhode Island. Carleston, SC: The History Press, 2013, pp. 105-110, 199-124; Luconi, Stefano. The Italian-American Vote in Providence Rhode Island, 1916-1948. New Jersey: Farleigh Dickinson University Press and Rosemont Publishing & Printing Corp. (Associated University Presses), 2004.

6 Jonata, Dante. "The Federal Hill House Persists, Altered by Times." The Providence Sunday Journal, 6 Aug. 1973, pp. B-1.

7 Lynch pp. 8.2.

8 Ibid pp. 11.1.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid pp. 11.2.

11 Ibid pp. 11.2, 11.29.

12 Ibid pp. 12.1-12.3.

13 Ibid pp. 12.4-12.6, 12.8-12.9.

14 Ibid pp. 11.4-11.5

15 Ibid pp. 11.5-11.7.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid pp. 11.21, 11.24-11.25.

18 Ibid pp. 12.7

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid pp. 11.7-11.8.

21 Ibid pp. 11.9-11.11.

22 Ibid pp. 11.3-11.4.